A Dongbei Story, in Three Parts

1.

Dad’s Childhood Home

![]()

二姑 stands where the family kitchen once stood. Changchun, 2023.

长春 In July 2023. I visited my father’s childhood home with my aunt, Zhang Shang Yi. The house was built in 1930 as a single-family residence for a Japanese bureaucrat during the Manchukuo period. After the Siege of Changchun in 1948–49 — a five-month blockade that left an estimated 150,000 civilians dead from famine — emptied Japanese homes were subdivided and redistributed. My grandparents moved from Inner Mongolia to Changchun in 1949, and in 1960 they moved into this building with their parents and young daughter.

By that time, the building had been divided into eleven units. My grandparents occupied a ground-floor apartment of roughly 80 square meters. They partitioned the space into three rooms organized around a 火炕 (kang) in the main kitchen. Fueled by coal, wood, and scraps of paper, the kang heated the adjoining bedroom platform where three generations of my family slept. At the 炕头 — the warmest end — my father’s grandparents lay. The children slept toward the foot. In that room, a centuries old technology of domestic heating entered the apparatus of a modern city, collapsing distinctions between countryside and capital, inheritance and reinvention.

My father’s unit within this home can be understood as a point of constellation — linking my ancestral past to the present day, linking rural technologies of domesticity to modern regimes of energy extraction and nationalism.

Today, the building is listed as a protected Historical Building by the Changchun Cultural Relics Bureau at 塘沽胡同 9 号. What was once subdivided for survival is now preserved as heritage — a structure that carries within its walls the layered architectures of occupation, famine, migration, and endurance.

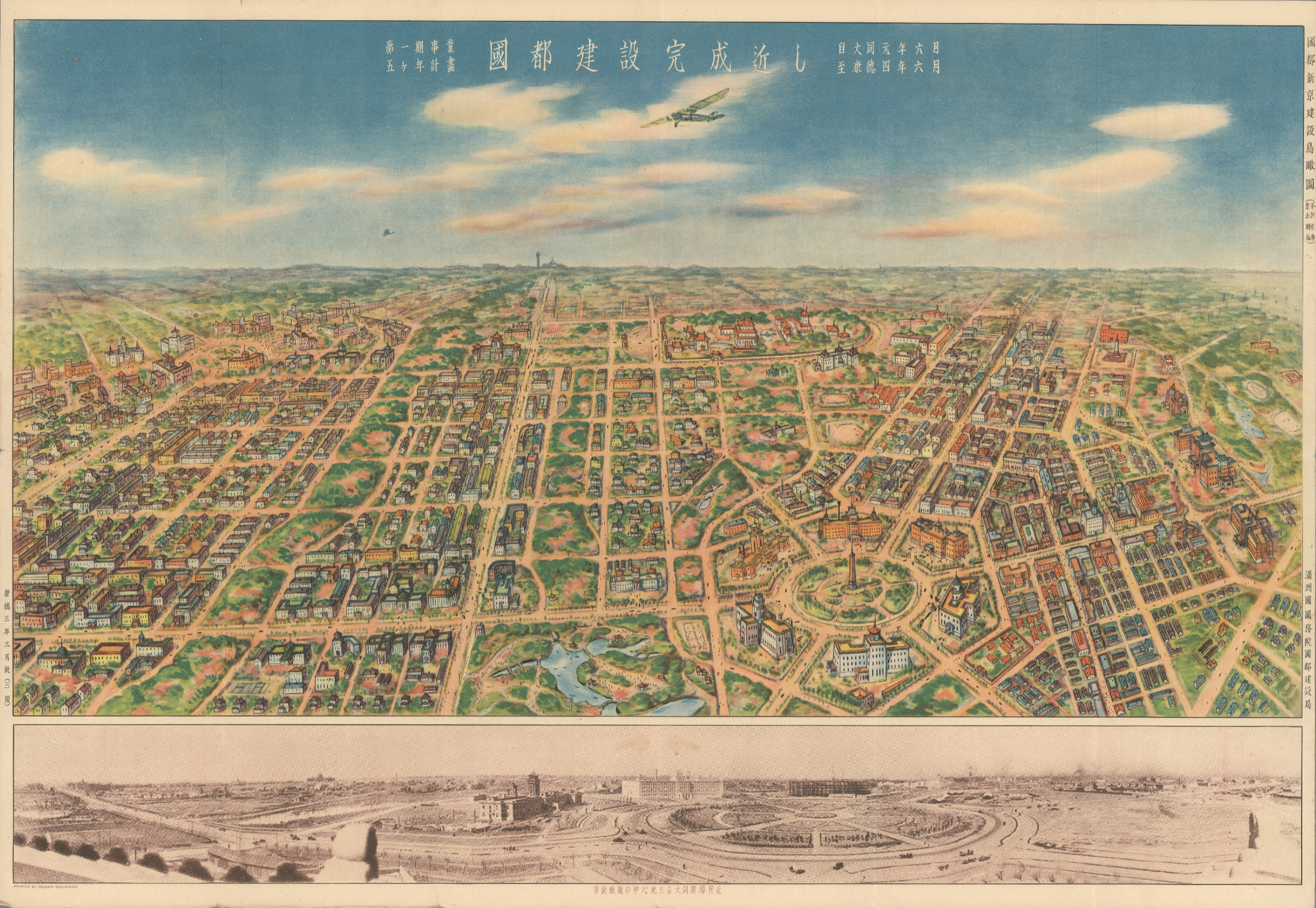

国都建設完成近し (Map of Shinkyo). State Council of Manchukuo. 1936. 大同广场 in the center right of the image.

Panaromic View of 新民广场 (renamed) and 人民大街 and it’s vicinity to my Dad’s Childhood Home. Google Earth. 2024.

2.

Water at the Foot of the Mountain

长白山 in July 2008. My memory of Heaven Lake itself is faint—rock spines, twisted trees, a sense of scale that never quite settled. What stayed with me instead happened lower down the mountain.

My late laoye, Qian Da Lin, a geologist who worked on emergent Chinese infrastructures in Central Africa, knew how to read rock. He had found a hidden spring just off the path. I had already run ahead, driven to find nature in its purest form first. By the time my mom caught up and told me about the spring, I was ecstatic—then devastated to learn my laoye and cousin had already returned to the visitor center. I cried, deeply and without restraint. It felt like I had missed something irretrievable: water untouched, straight from the source.

To console me, my laoye led me behind the visitor center. There, a small plastic pipe ran along the concrete wall, pouring out clear water. I was unimpressed. This wasn’t it, I told him. Still, I filled my bottle. As I drank that water, which still feels as cold in my memory as it was that day, my laoye traced his finger along the windy pipe as it snaked back up the hillside. He shrugged—it was the same source, he said, just redirected.

3.

Mom’s TV Show, Learning to Draw

吉林电视台 专题部 — 学习画画节目. Jilin Television Station — Special Programs Department. 1986.